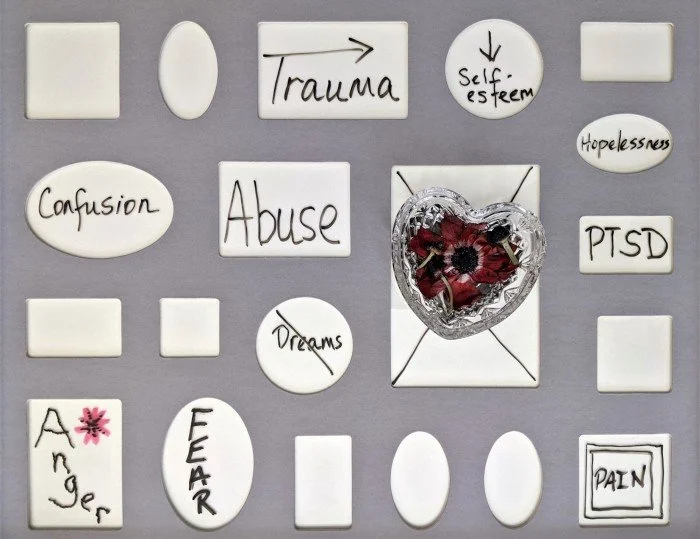

Image by Susan Wilkinson

It’s never been easy to share the details of my parent’s deaths with others. As outlined in my upcoming book, Daddy, when I was twenty-eight my father shot my mother and then committed suicide. Though I didn’t directly witness the shootings, I was the only other person in the house at the time. I heard the shots, found their bodies, and dealt with the hours of police questioning that followed. As a result, I developed PTSD.

In the months that followed, I felt compelled to disclose the details of this tragedy to just about everyone I met. Strangers, acquaintances—it didn’t really matter. My life had suddenly and irrevocably changed in ways I couldn’t fathom and I didn’t know what I might be capable of. I’d find myself choking up with tears or manically going on and on over some small thing for no apparent reason. These moments were off-putting to others and often left me feeling embarrassed. I thought these disclosures might be a way to help brace people for potentially erratic behavior.

I was also responding to my feeling that I had become a bottomless well of need. I secretly hoped these disclosures would draw people into my orbit where they could provide much needed comfort and understanding. For strangers, this strategy was doomed to backfire. I still remember the wide-eyed, fearful reactions of bank clerks and realtors in response to my casual mention of such shocking and intimate information.

Many acquaintances were quick to offer practical and emotional support during the initial crisis, but the ongoing heavy lifting of dealing with someone in the depths of PTSD eventually sent them all running for the hills. While my small circle of friends and family initially made an effort to roll with my depressed and erratic moods, they were on a highly unrealistic timetable, expecting I would somehow show improvement within a couple of months.

It actually took the better part of ten years to pull myself together. By that time, I’d become extremely isolated. After having lost several friends to AIDS and going through a couple of ugly break-ups, I was effectively alone in San Francisco. The relationships with my family were cordial, but they lived thousands of miles away and were focused on their own lives. Over those years, I’d reached the conclusion that sharing the facts about my parent’s deaths was just not worth it.

Why put yourself out there only to be hurt and disappointed?

It finally dawned on me that pursuing goals for my personal development—things like graduate school and a career—were a more reliable path to recovery than trying to depend on the fickle support of others. However, even this path was paved with daunting roadblocks.

I’d been rejected on my first attempt to return to school because I completely went off track during the interview process. Spacing out—aka dissociating—from the extreme anxiety of the situation, I clearly remember trailing off, not even finishing many responses. I took it hard, but reapplied the next year, cinching the interview the second time around. Nevertheless, I was waitlisted. When I got the call that I could start in the fall, I shared my surprise with the admissions officer. She briskly replied that she, too, was surprised I was being admitted.

Clearly, I wasn’t off to an auspicious start. Things only got worse. I quickly developed the type of insomnia that left me wide awake for two or three days at a time. I couldn’t focus and was confused by the complexity readings I’d been given. I felt deeply depressed and wildly insecure.

As part of my school’s program, I was assigned to a training group with seven other students. The group was to remain together for our first two years and was led by a faculty member who was also a psychologist. During our weekly meetings, we discussed cases and provided support and feedback to one another. People also brought in personal matters that were impacting their work. Here, I thought, might be the place where like-minded people could appreciate the impact trauma was having on my life.

I decided to share with the group what had happened to my parents. I hoped my disclosure would deepen these relationships—to help people see me more clearly. They might even admire how well I was doing under the circumstances.

While I received general acknowledgement and brief empathetic comments, a few minutes later another student shared that she had been struggling with the anniversary of her step-father’s death from cancer. It became all about her. None of this led to anyone checking in to see how I was doing, asking me out to lunch, or sharing greater intimacies and support afterward.

I wished that I’d gone about things differently, imagining there must be a better way to present this more vulnerable side of myself without the stakes feeling so high. Still, I felt hurt and resentful. I couldn’t understand why some people garnered the concern and caring of others as naturally as they soaked in the warmth of the sun. Once again, I withdrew into myself.

The program also required students to complete part-time internships—usually at a community mental health clinic or college counseling center. In addition to providing therapy to patients, these internships involved on-site group training. During my second year, I learned that an upcoming training would be led by a postdoc—a student a few years ahead of me who had already graduated. She would be drawing our personal genograms on a white board as part of her presentation (a genogram is a diagram of your family members, how they are related, and their medical history. The goal of a genogram is to help people understand patterns of behavior and other psychological factors that run through families).

I debated for days over whether to share the truth about my parent’s deaths. I’d been burned before—it would’ve probably been easier to act like they were alive and well, living out their golden years in Palm Springs. However, when it came time to map out my family, I decided to take a chance and tell the truth about their deaths. I’d grown close to the other interns and felt the waters were somewhat safer than they had been the previous year with my other training group.

I watched as the postdoc drew little circles up on the white board with my parent’s names in the center. I shared that they were no longer living. As she drew slash marks across their names to denote their deaths, she asked how they died. The labels “murder” and “suicide” were written below their names. No one made a comment. The postdoc and psychologist who led the group didn’t ask if I was doing okay or express any sympathy. We moved on to my other family members. Soon, my turn was up.

No one said a thing about my disclosure afterwards—or ever. Did any of them consider how exposed I felt? Were they too afraid or too uncomfortable to say something? Once again I felt ashamed for putting myself out there. My experience had been completely devalued by people who should know better.

Did they just not care?

Around that same time, I started working with a therapist who was able to demonstrate through her words and a thousand non-verbal expressions that she truly understood the terrible gravity of my situation. The sense that she “got it” helped to restore my trust in others. She helped give meaning and clarity to experiences that had twisted me up in knots since the day I’d found my parent’s bodies. As such, I was able to process the trauma to the point where it was not ever-present in my mind.

I’ve now reached an age where questions that are normal when you’re younger—What do your parents do? Where do they live?—rarely come up. Today, I seldom tell new people about them. Through luck and perseverance, I’ve been able to develop a few intimate and supportive relationships with people who understand the details of my traumatic experience. Where it once felt like to know me you must know my trauma, I now feel like there are so many other important experiences that better define me.

Through my work with other trauma survivors, I’ve come to realize that there is something about trauma that causes many people to turn their backs when confronted with our terrible stories. We are at risk of becoming a representation of their worst fears or a reminder of their own traumatic histories. Many fear being overwhelmed by our needs. I’ve also come to recognize that people often respond for reasons I could never guess—no matter how hard I tried. My fatal mistake was to make the assumption that their reactions implied there was something fundamentally wrong with me. But being treated like your experience has no value doesn’t mean you’re nothing.

Today, the motives behind publicly sharing these anecdotes stems from my wish to help other trauma survivors. With my support system and self-esteem (mostly) restored, having the details of my traumatic experience validated by others doesn’t feel nearly as urgent as it once was. What’s truly gratifying about my role as a psychologist and a writer is seeing other people’s response when something I’ve disclosed hits close to home. In those moments, I feel truly connected—confident that I’ve transformed my story into something useful to others.